“Git a pass”: Paul Revere and the Siege of Boston

By Nina Rodwin

Historians have a clear picture of Paul Revere’s activities and whereabouts during the Midnight Ride, but there is much less information regarding his actions during the week after April 18, 1775. Letters from Revere’s wife, Rachel, suggest that Paul may have returned to his home at least once. A few days after Revere’s ride, Rachel wrote to Paul, hoping that he would “take the best care” of himself while also warning him “not [to] attempt coming into this towne [sic] again.”[1] Rachel’s plea missed its mark, however, as the letter never reached him. Unfortunately, Rachel had enlisted a fellow Son of Liberty, Dr. Benjamin Church, to send the letter, not knowing that Dr. Church spied for the British and would turn the letter over to General Thomas Gage. Rachel’s correspondence to Paul illustrates the general uncertainty and fear that many families felt, as she reminded her husband to “trust your self & us in the hands of a good God…for vain is the help of man.”[2] Like many families in Boston, the Reveres began to plan their escape out of the city.

As British soldiers returned to Boston on April 19, General Gage began preparations to evacuate civilians. Gage initially ordered that inhabitants of Boston could leave after they handed over their firearms.[3] Revere’s 15-year-old son, Paul Jr., was recorded handing over two muskets on April 27.[4] Gage’s policies rapidly grew more restrictive; families could only bring essential items and would be forced to leave any merchandise behind. Since many families during this time had their wealth tied to their land or business, this order would have undoubtedly caused a great deal of anxiety. General Gage limited the number of wagon drivers entering the city to just thirty a day, meaning that many families were forced to leave the city with only the things they could physically carry. To make matters worse, Bostonians would not be able to return once they left. Not only did families have to risk abandoning their homes and livelihoods, they had no way of knowing when (or if) they would ever return.

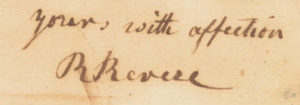

During this confusing time, Rachel Revere searched for a pass. These passes were similar to permission slips – evacuating families needed to show they had received approval to leave the city. Revere family letters demonstrate that obtaining a pass was not an easy task. About a week after his ride, Paul wrote to his family, instructing Rachel to bring their “most valuable” possessions first, including “Bedds [sic] [mattresses]. . . my chest, your Trunk with Books, Cloath [sic].”[5] Revere’s letter also shows his generous and caring side- Revere wanted his sisters and mother to know that regardless if they stayed in Boston or evacuated, he would “supply them with all the Cash & other things. . . in my power to provide for them.”[6]

Revere’s letter illustrates that he was worried about his workshop and home. Since Revere could not take his tools or merchandise with him, he asked Rachel to contact Isaac Clemmens, a fellow silversmith, who belonged to a Tory military unit. Revere wanted Clemmens to “take care of the shop” as a way to protect his business.[7] To protect his house, Revere asked Paul Jr. to “keep your self [sic] at home.”[8] However, it is unclear if Paul Jr. actually spent much time living alone in the house. In Jane Triber’s study of the Siege of Boston, she notes that Paul Jr. likely had support from his grandmother, aunts, or even his cousins in the next-door Hichborn home. It is unclear if the extended family moved into Revere’s home, or if Paul Jr. moved into one of his aunts’ homes, but it was likely reassuring for Paul and Rachel to know their son was not entirely alone.

Although it is unknown exactly when Rachel and her family reached Watertown, letters demonstrate that the family struggled to obtain a pass. On May 2, 1775, Rachel admonished Revere after he reached out to the British officer Captain Irvin for a pass. Demonstrating her political views, Rachel felt that it would be better to “confer 50 obligations on them than to receive one from them.”[9] Despite Rachel’s frustration, her letter suggests that she may have bribed Captain Irvin for a pass, as she notes the letter was delivered to the Captain with “2 bottles beer 1 wine.”[10] The next day Paul received a letter from his Masonic friend Ezra Collins informing him that Rachel “expects a pass this morning.” When Rachel and her six children arrived in Watertown they moved into what is now known as the John Cook house, which stood at the modern intersections of Watertown and California Streets.[11] Revere and his family lived in the home with Henry Knox, his wife Lucy, and Boston printer Benjamin Edes.[12] It’s likely that being around friends was a comfort for the Reveres during these uncertain times.

Through their professions, Edes, Knox, and Revere were each able to lend useful skills to further the revolutionary cause. As the printer of the Boston Gazette, Benjamin Edes had published numerous incendiary pieces against the British Government’s policies, including the detested Stamp Act. His newspaper encouraged revolutionary efforts to such an extent that the Royal Governor Francis Bernard threatened to arrest him for sedition. Some of Revere’s engravings were featured in the Boston Gazette, including his famous engraving of the Boston Massacre. Henry Knox joined the Continental Army and became well respected after his successful expedition to Fort Ticonderoga in 1776. He eventually became one of Washington’s most trusted deputies and ultimately served as the nation’s first Secretary of War.

While in Watertown, Revere also used his many talents for the cause. The Provincial Congress instructed Revere to print currency. As a skilled engraver Paul could easily create designs for the paper money on copper plates. Once these engravings were completed, Revere would go to the Edmund Fowle House, where the engraved notes would be signed by the Executive Council. Printing currency gave Revere’s family a steady income and helped him gain further influence as an entrepreneur and businessman. Additionally, Revere continued his work as a courier for the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Couriers were not well paid, but served an essential purpose as an early postal service. Revere delivered letters to families around Boston and sent messages to and from fellow Sons of Liberty.

Besides Revere’s work for the Provincial Congress, we know very little about how his family spent their time. It is likely that the most challenging aspect of the Reveres’ life in Watertown was the general uncertainty. Contemporary audiences are well aware that the Siege of Boston ended, and that the Revolution was eventually successful, making it easy to overlook the fact that at the time the outcome was unknown. There was no guarantee that the war would bring independence, and it must have been painful for the Reveres to not know if they would ever see their home again.

The Reveres returned to their home a year later, after British troops left Boston on March 17, 1776. While moving back to their home was likely uplifting for the family, their return was also tinged by sadness and pain. Paul’s close friend and fellow Son of Liberty, Dr. Joseph Warren, had died at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Charlestown was in ruins, and hundreds of families and businesses around Boston were still displaced. Despite the challenges after the Siege, Revere’s business would recover, as he found new ways to serve the public and his country.

[1] http://ur.umich.edu/0405/Apr18_05/14.shtml

[2] Ibid.

[3] Historical Background on the Siege of Boston – Jane Triber

[4] Ibid.

[5] Revere’s “lost letter,” taken from PRH Gazette Fall 2014 No 116.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Historical Background on the Siege of Boston – Jane Triber

[8] Revere’s “lost letter,” taken from PRH Gazette Fall 2014 No 116.

[9] Historical Background on the Siege of Boston – Jane Triber

[10] Ibid.

[11] The Edmund Fowle House During the Revolutionary War – Watertown Historical Society. http://historicalsocietyofwatertownma.org/HSW/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=63

[12] The Edmund Fowle House During the Revolutionary War – Watertown Historical Society. http://historicalsocietyofwatertownma.org/HSW/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=63

Nina Rodwin is an interpreter at the Paul Revere House