Special Guest Scholar Post: Ties that Bind – Paul Revere, Jr. and the Power of Relationships

By Jeannine Falino

A Note from the Executive Director

While the intent of the Revere Express blog is to showcase our staff’s work, we also intend to share the work of fellow experts in the field from time to time. So, I am thrilled that our first “guest” post is authored by none other than our good friend, esteemed colleague, and PRMA Council member, renowned silver expert and fine arts consultant, Jeannine Falino. I am sure you will enjoy her analysis of the impact of Revere’s networks on his silver shop business. -Nina Zannieri

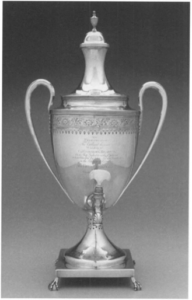

Paul Revere, Jr. (1734–1818), urn, Boston, Massachusetts, 1800. Silver with ivory spigot handle; h. 19 in. Massachusetts Historical Society, Gift of Helen Ford Bradford and Sarah Bradford Ross. [photo MFAB]

If we take a bird’s-eye view of eighteenth-century life in Boston, Paul Revere was one man, a craftsman who was the master of a single workshop. Yet he seemed to be everywhere at once, connecting with people from all walks of society. His activities, before, during, and after the American Revolution demonstrate that he stood at the intersection of the town’s social, economic, and political life. And therein lies this tale of connections.

Revere’s success was in large measure due to the powerful web of relationships that he developed during the course of his career. By turns, familial, social, religious, and political, each circle or group signifies the silversmith’s varied interests and activities. It also represents a potential consumer base. While this might lead some to think that Revere’s actions were those of a calculating businessman, it is more likely that these customers were a collateral benefit of his active life. Revere was an enthusiastic joiner, leader, and worker. If the Rotary or Lions Club had existed in colonial Boston, it is likely he would have joined them as well!

Proving this premise has required an examination of Revere’s two daybooks (also called wastebooks or ledgers) dating from 1763 and 1797, and surviving silver found in museums, private collections, and auctions to establish the largest known list of the silversmith’s customers. Although it is an incomplete assemblage, the 757 known individuals make further linkages to Revere possible through the lens of their memberships and associations.

Starting with the closest relationships, Revere’s family provided a modicum of support to his shop, especially from the Hichborns on his mother’s side of the family. A few orders from early in his career were made by his father’s former patrons. Others came from neighbors, among them the hatmaker Ezra Collins from nearby Clark’s Wharf.

Next was New Brick Church on Middle Street (now Hanover Street) in the North End, which was close to Revere’s childhood home. Revere belonged to its senior church committee from 1787 to 1803, and while he did not produce communion silver for New Brick Church, nearly a third of the membership (27%) patronized him. The most notable purchase, a large and costly presentation urn in the neoclassical style, seen above, was made by Revere’s fellow committee member, the wealthy merchant Samuel Parkman. Church customers included successful craftsmen and tradesmen like the blacksmith Enoch James, and the blockmaker Thomas Lewis.

The Freemasons formed a particularly important group of patrons for the silversmith, bringing him considerable business over the years. Due in part to his long association with Saint Andrew’s Lodge, 64% of his fellow members were patrons. Masons and lodges located in New England and elsewhere constituted about one third of his entire business altogether. While some items such as crossed keys and crossed pens worn by officers were for Masonic use, most recorded purchases were for personal goods that ranged from tea sets and spoons to simple mending.

Colonial loyalty to the Crown began to erode rapidly after the Stamp Act of 1765, and while Revere was an active Patriot, he didn’t allow politics to get in the way of business. Like the Boston painter and English sympathizer John Singleton Copley, Revere accepted work from customers on both ends of the political spectrum. British commander Thomas Gage sat for Copley in 1768, the same year that Revere sat for his own portrait and produced the Liberty Bowl. And in 1773, shortly before the Boston Tea Party, Revere completed the largest commission of his career with a forty-five-piece tea service for Dr. William Paine of Worcester, who served as a physician with British forces during the Revolutionary War.

As political tensions increased, Revere was willing to aid the Patriot cause by whatever means possible. His activities brought him into contact with nearly all of the revolutionary organizations in Boston, even those to which he did not belong, such as the Boston Committees of Correspondence, an elite body formed in 1772 by Samuel Adams, and the Loyal Nine, the Boston artisans and shopkeepers who were the initial core members of the Sons of Liberty. The Sons of Liberty membership included Harvard-educated lawyers, doctors, ministers, and merchants drawn from the professional ranks. In this group, about 22% purchased silver from Revere. Among the well-to-do clients in this group was Perez Morton who was a member of the North Caucus and attorney-general of Massachusetts from 1811–1832. Over sixteen years, beginning with his marriage in 1781 to the poet Sarah Wentworth Apthorp, Morton purchased a nearly complete tea service from Revere.

In the years after the American Revolution, Revere continued his leadership activities by becoming a founding member of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA) in 1795. While not as wealthy as lawyers and merchants, this organization represented a leading segment of the solid middling class. They elected Revere, by then the most notable and respected artisan in town, as the Association’s first president. And as with his other relationships, his fellow members could be counted among his customers, such as the bricklayer Jonathan Hunnewell, who became the Association’s second president in 1800. One year after the MCMA’s formation, Hunnewell ordered a silver service consisting of twelve teaspoons, one pair of sugar tongs, a teapot and stand, sugar basket, and four salt “shovels,” the hollowware executed in the newly fashionable fluted neoclassical style.

Many of Revere’s patrons have been identified according to the social relations they shared with the silversmith. His membership in the Masonic brotherhood, his patriotic alliances, family, friends, and church relations all had some bearing on the relative size of his customer base. For those of us now sheltering at home, Revere’s energetic participation in Boston life reinforces the interconnectedness that makes life so rich and full. Let’s use Revere’s example during these sequestered times to reach out to our family, friends, and colleagues, and renew our commitment to each other. The benefits are immeasurable, and maybe a bit contagious!

- This essay is excerpted from Jeannine Falino, “‘The Pride Which Pervades thro’ every Class’: The Customers of Paul Revere II,” Colonial Silver and Silversmithing in New England, 1620–1815. Boston: Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, v. 70, 2001. The essay above is written and published with permission of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.